Recently, the idea of learning in the open has been on my mind a lot.

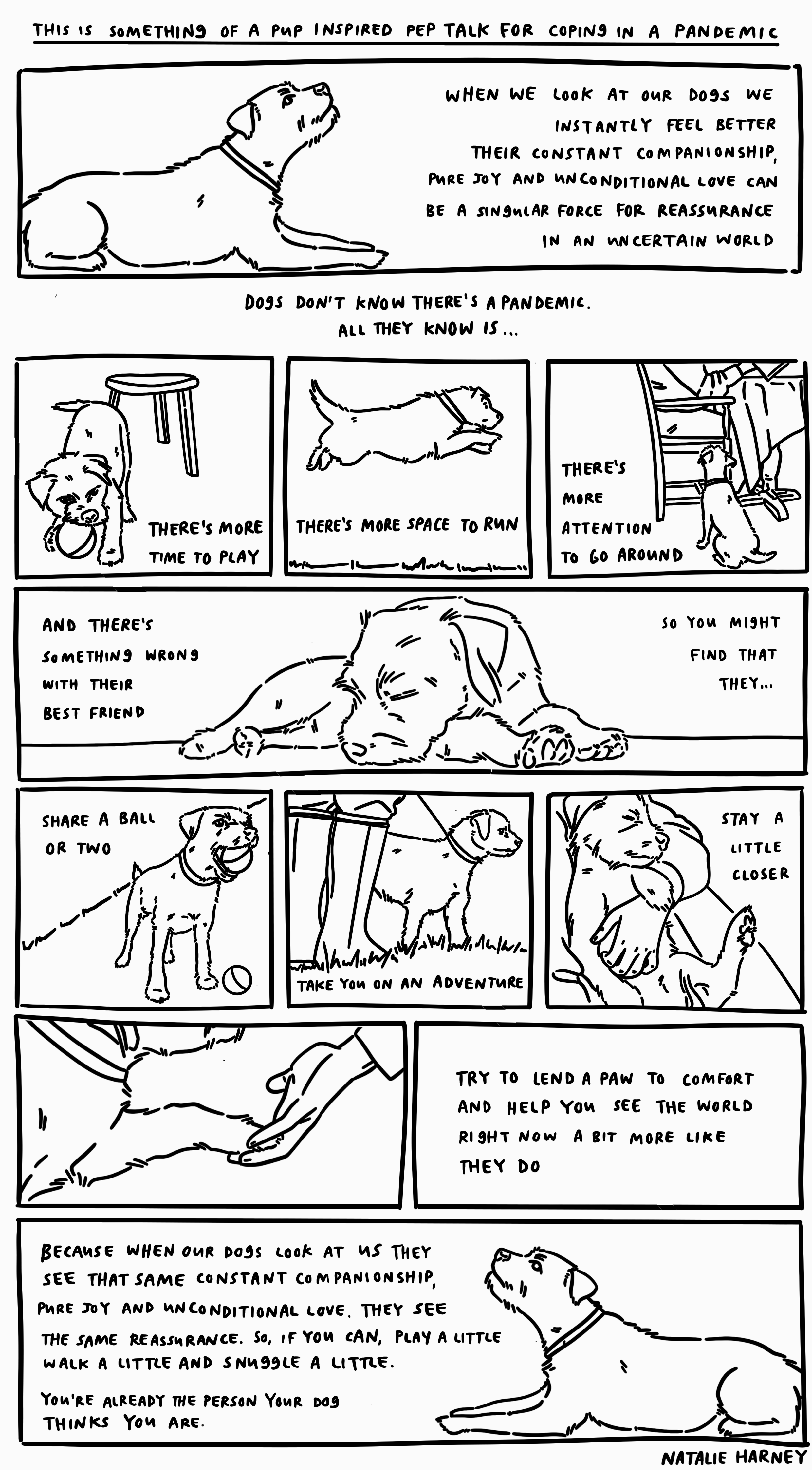

There have been two main drivers. First, I’ve personally felt and heard lots of other people talking about a fear to say the wrong thing in regards to Black Lives Matter, not because we didn’t believe the message or want to fight for justice and equity, but because there seemed to be so many ways we might get it wrong while we tried to learn to be better allies in the open. Second, I’ve been drawn to making more and not wanting to share it here or on social media, because I wanted to feel free again.

This blog is probably the closest I’ve gotten to truly learning in the open. I was always the kid who wouldn’t share work until it was done. But here, in part because of the fact I’ve been sharing for years, there are plenty of learnings in progress that I’ve shared in case others are on the same journey for want of a better word.

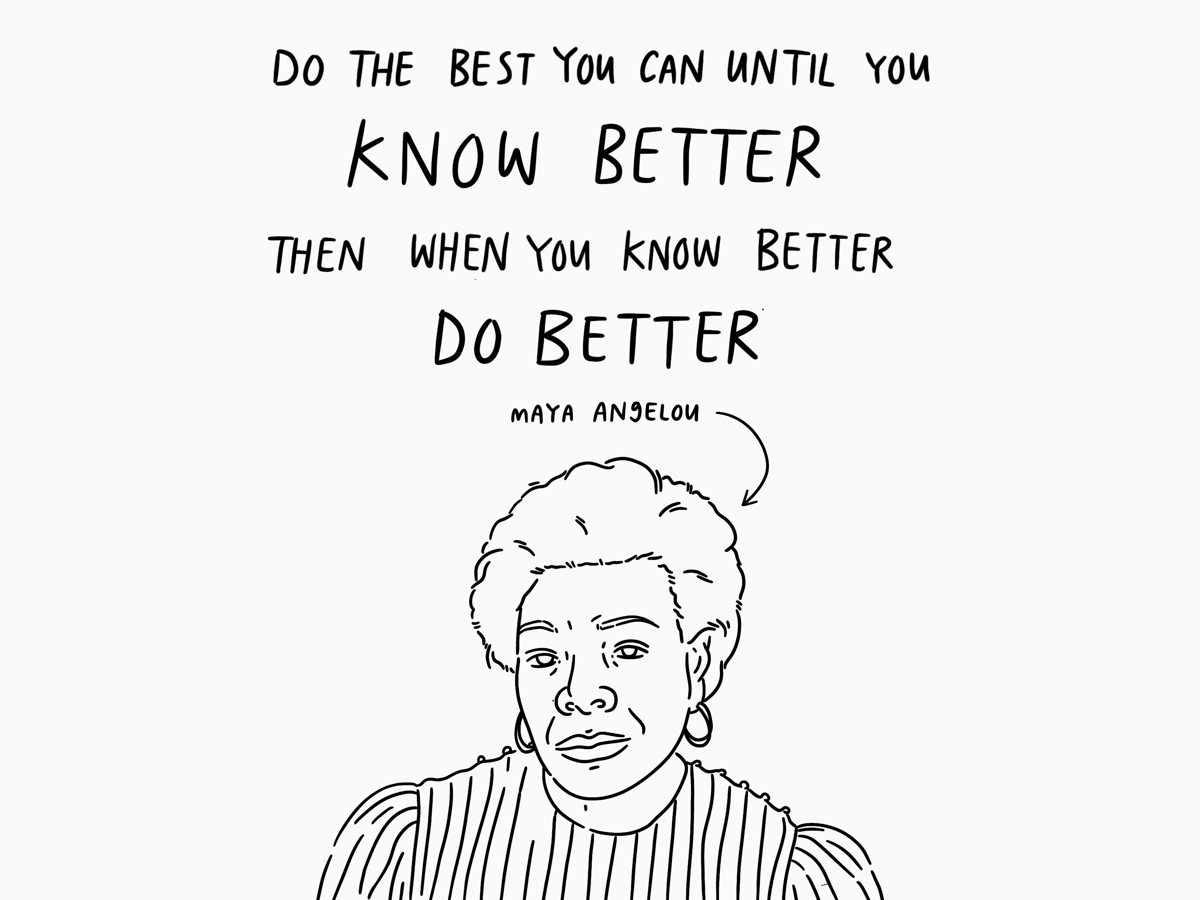

Yet as much as I know those moments of learning and growth were important to getting me to where I am today. I very rarely reshare them, because I’ve changed since and because I wouldn’t want this blog or me by extension to be judged on what I thought 3 years ago. I’m sure I’ll probably think the same about this in 3 years too.

When you learn in the open online, there’s always a record. That record can be searched and brought up years later, for better or worse. How many times have we seen someone ‘cancelled’ because of something they tweeted years before whether they had grown since or not?

However, if we never learn in the open and we never share how slow progress can be surely it dissuades others from even starting the process. If you can only be an expert or a master of a craft or nothing, where is the recognition that no one gets there overnight, especially when it’s learning that has to be done outside of the classroom.

So, largely for myself, I wanted to make the case for both learning in solitude and learning in the open, to try to work out which I want to do.

The case for learning in solitude

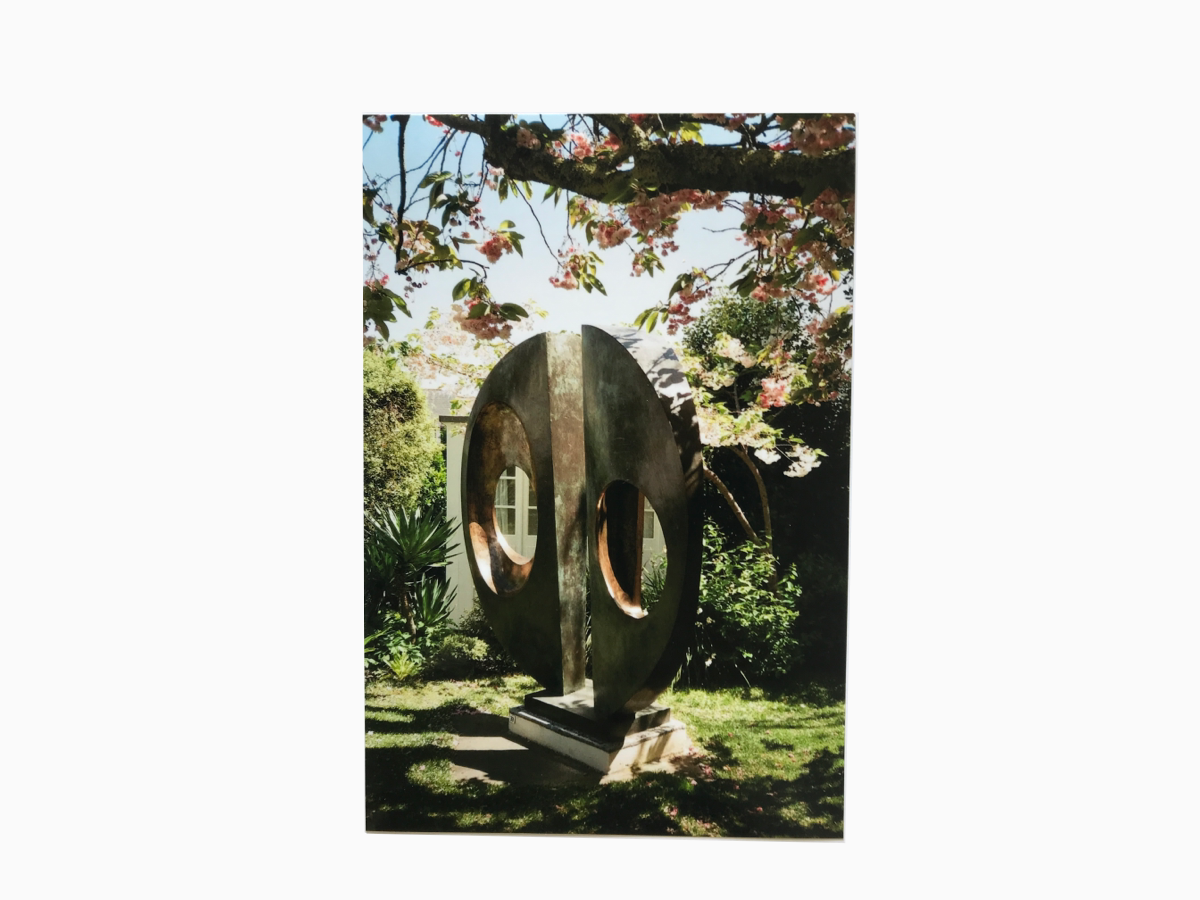

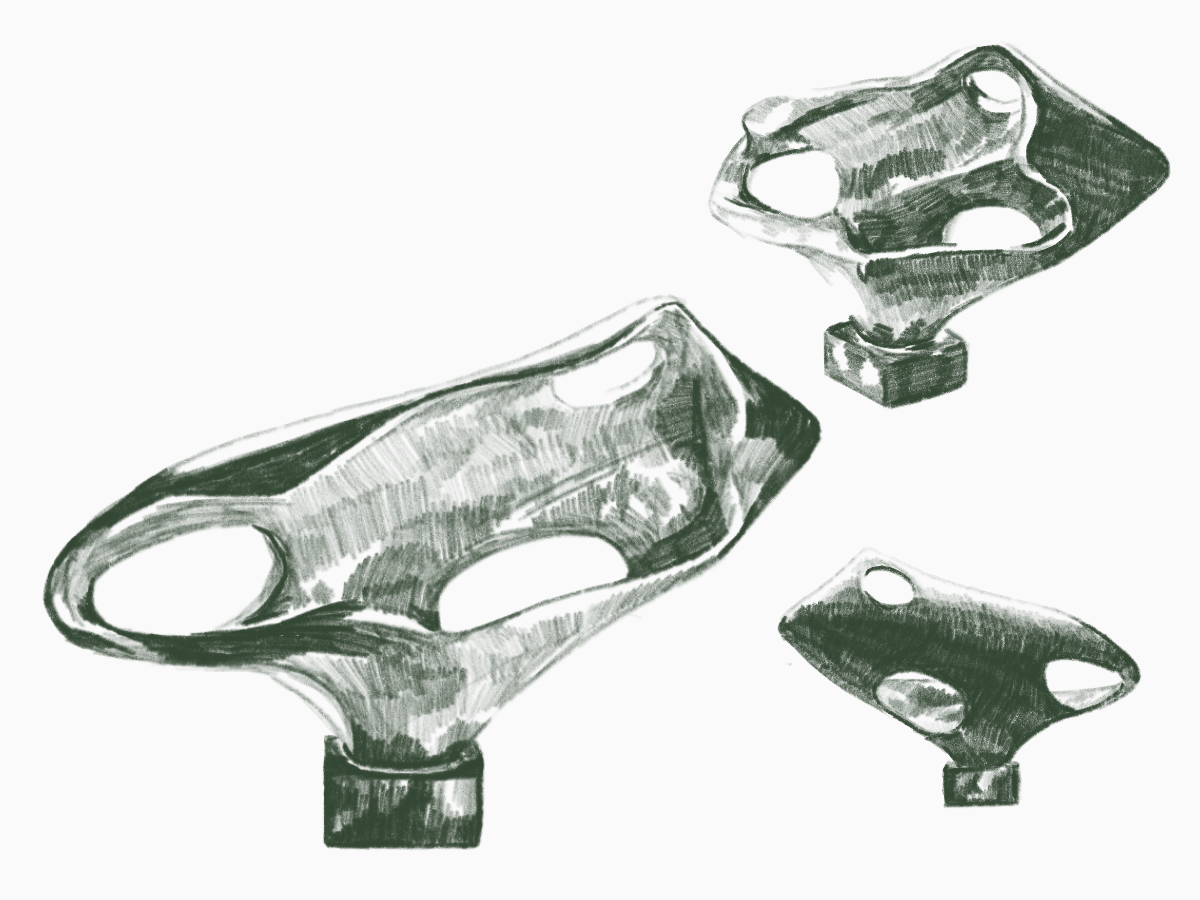

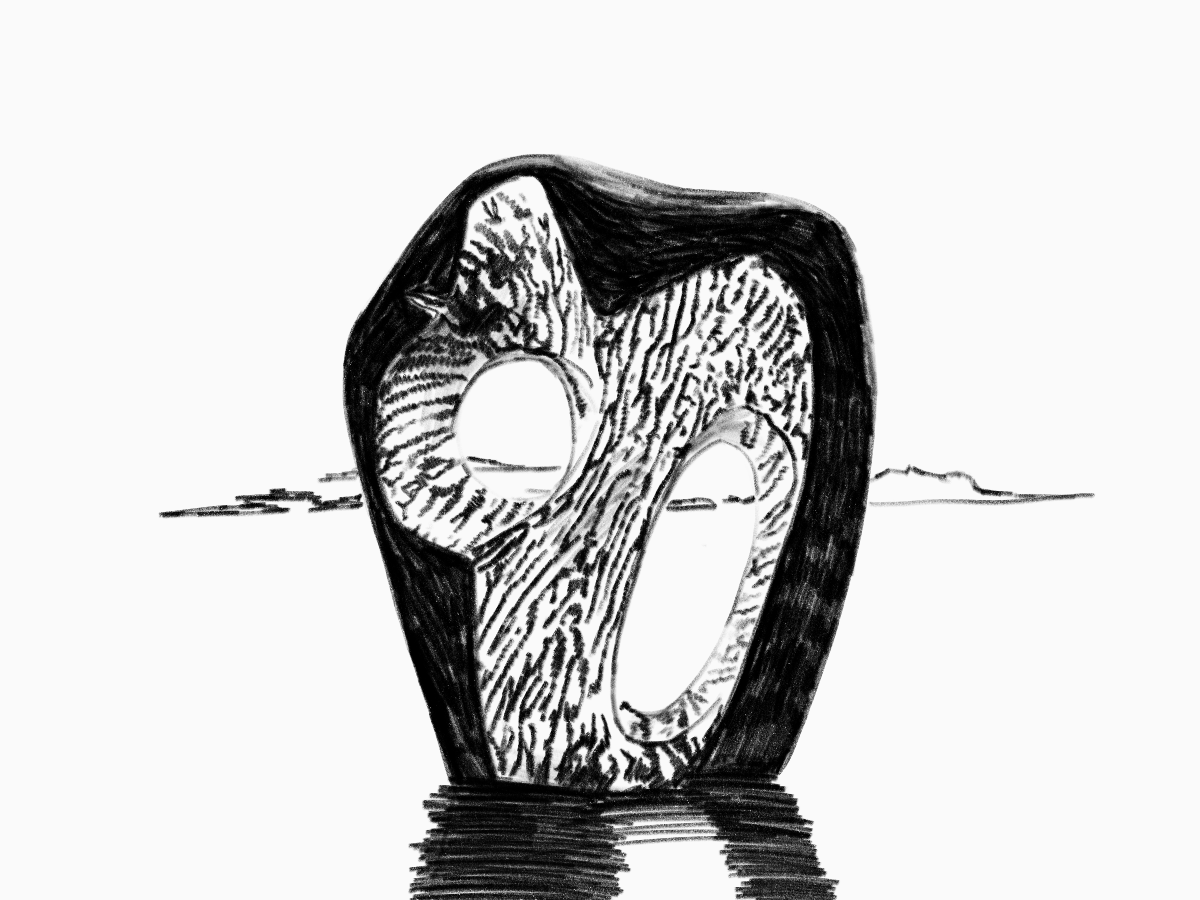

Away from prying eyes, you can experiment free of judgement. You can go wherever your learning takes you with no responsibility or sense that it needs to conform. This freedom can be particularly liberating when it comes to creative work. Sketchbooks that include tests and scraps can inspire bigger works, without needing to be finished pieces themselves.

You are free to shape your own opinion on the subject matter, following your reading and intuition. You are in charge of your own curriculum and can draw connections between whatever insights you’ve found, without a sense of needing to fit them into convention.

When it comes to learning more important topics, if you take the time to learn on your own, to make your own progress, you may be less likely to say something out of turn that could hurt others.

The case for learning in the open

When you learn in the open, you lose some of that self-initiated freedom. But you gain the potential to be challenged and to be introduced to new ideas that you might not have found yourself. You might be directed to different subjects or course corrected by someone with lived experience.

Someone might see something in the works in progress that you share that you might not have seen on your own, whether that’s their good or their bad qualities or their harmonies with other works.

Someone might also resonate with your progress and be inspired to make their own, seeing how far you’ve come or how close you are. You might learn together. You might learn in parallel. You might lead their learning.

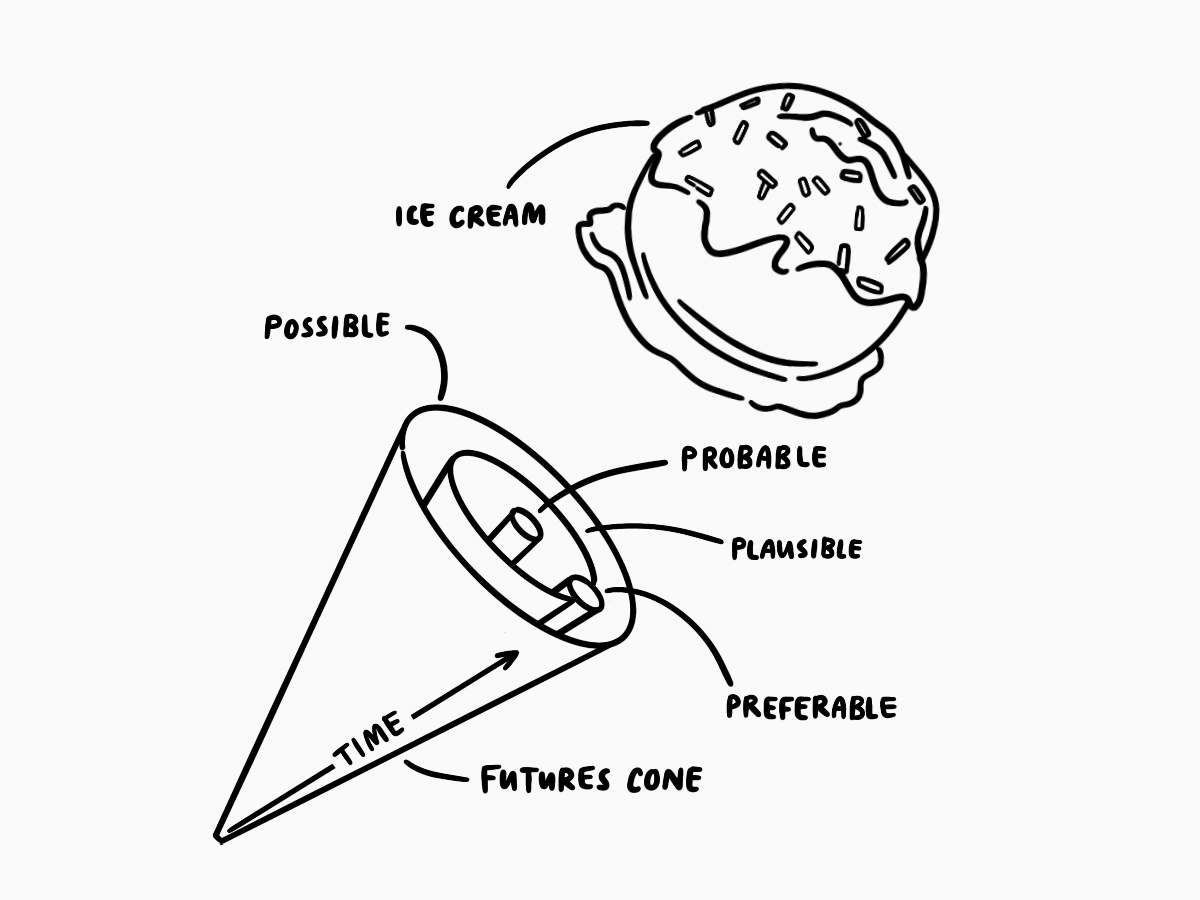

Learning in the open and learning in solitude have their pros and cons. Depending on what you’re learning, how you’re learning and why, you might find one or the other works best for you.

I typically end up doing something of a hybrid between the two; I spend time getting to grips with the basics alone then share what I learned in hindsight. I think that’s where I’m likely to stay for the majority of my work.

That said, I don’t think we shouldn’t share because we are afraid to fail. There is so much value to having a space to play and learn and experiment on your own. But there is so much more to be lost from never learning in the open because we feel too fragile to accept a stumble or a critique.

I have definitely fallen into that camp, and oftentimes still do. I was an overachiever at school and now my sense of self can be so fragile that the slightest perception of failure threatens the careful balance I’ve been working on since I was 5. That’s something I’m working on. That’s something I think we should all be working on.

We need to normalise receiving new information and changing our opinions. We need to practise taking feedback (and giving feedback) in a way that’s positive and not defensive. We need to find a way to make it okay to be a work in progress in the open again, because that’s what we all are, works in progress.