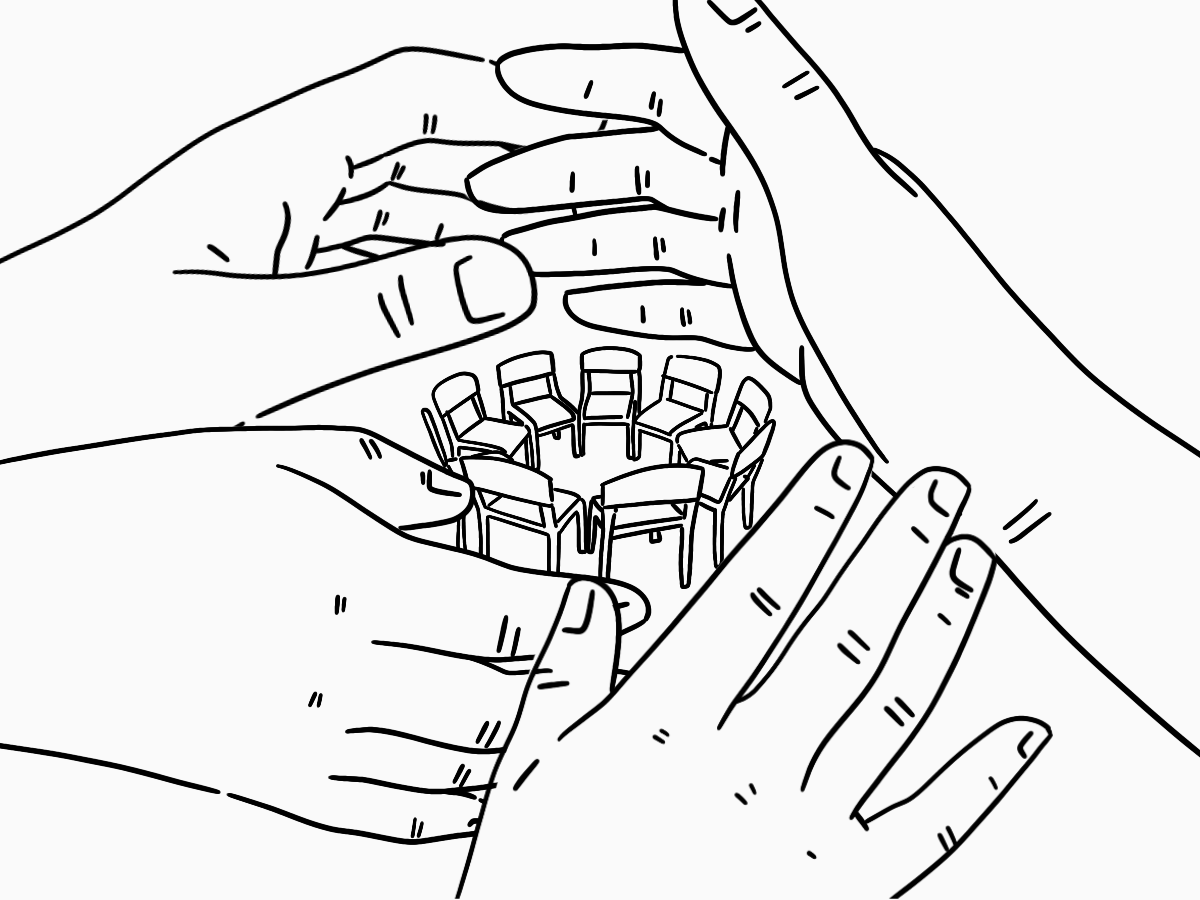

For the last year and a little bit I’ve been a member of ENGINE UK’s shadow board. ENGINE is a full stack agency which covers creative, communications, media and transformation, essentially it’s like a creative marketing and comms powerhouse that works hand in hand with data and consultancy know how. The shadow board was an opportunity for 9 of us from across the business to come together and shape the future of where we work, support our executive team and ultimately see what it means to be a leader in a different context.

As my time on the shadow board is drawing to an end, I wanted to put together some personal reflections alongside the group work we’re doing to support next year’s cohort and share the good stuff we’ve learned.

This was the first time ENGINE had ever had a shadow board. Well, in fact, a junior board which we swiftly renamed a shadow board. So we didn’t really know what to expect.

We went through a long recruitment process, sharing written submissions, doing hot seat interviews and group tasks all to find a group that could represent the diversity of disciplines and voices in the business, and who would hopefully work well together too. Our purpose became championing the voices of our colleagues and sharing what it was like “on the ground”, offering fresh energy and expertise to central projects, and spending time learning about the business. Alongside still doing our day jobs!

It’s been a full on experience, with highs and frustrations.

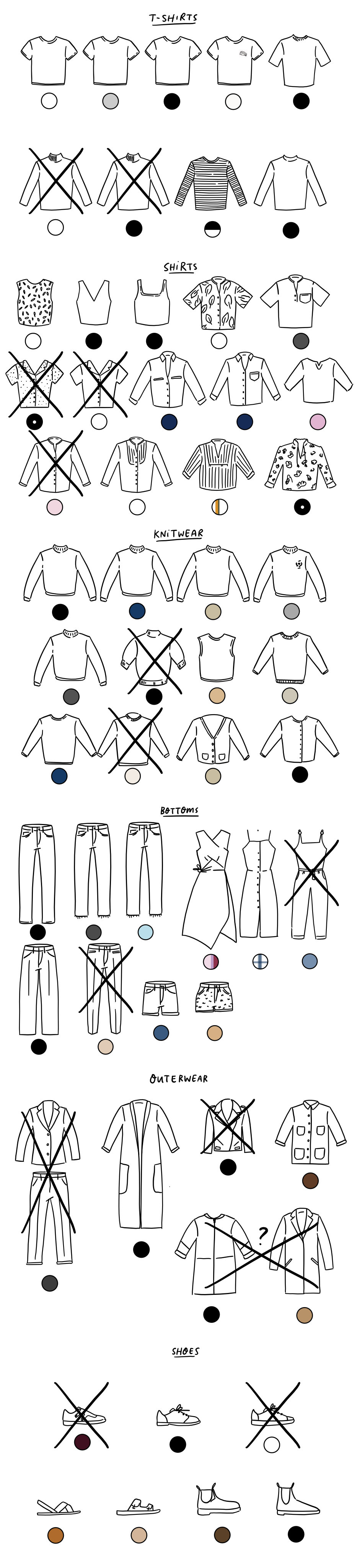

We launched a new intranet. We rejuvenated our onboarding processes. We put plans in motion to make ENGINE culture much more active and physically present, before COVID put a little spanner in the works. We researched and designed new career progression guides. We tried to make sense of what the pandemic will mean for us as people and a business. We learned from Jim our CEO. We learned from each other. We learned more about ourselves.

Professionally, I learned a great deal about what makes a big people-centred company like ours tick. I don’t think I had ever really stopped to think about the decisions our exec made day to day, there was a lot more tactical management of the stuff that’s the “boring” fabric of the business than high flung strategic work. But the more I saw, the more that made sense. You need that fabric to be woven tightly if you’re going to use it as a sail to take flight. There’s a constant tug and pull as you go, trying to balance priorities and budgets. But ultimately it comes back down to working with people.

I learned more about how the other parts of our business work than I thought I would. Having been on a graduate scheme where I spent a year rotating around different sections of the company, I thought I had a good handle on what we did. But the time I spent with my other board members, reviewing training plans or trying to come up with cultural events, made me realise how different our approaches to problems can be. There are a lot of similar foundations in what we do (research, insight, strategise, produce something that resonates) how a group of PR people can hive mind a brief when they’re together, how a group of strategists will research and analyse it, and how a group of designers will immerse themselves and workshop it can look and feel very different. They’re each incredibly valuable and I’ve been made much wiser by watching other brilliant people work.

But I really wanted to reflect here on a personal level. If there’s one thing that will stick with me long after this experience, it’s that things are what you make of them.

It’s the most obvious lesson and also the hardest (for me) to put into practice. As I mentioned, when we started our time on the shadow board we weren’t really sure what it was. We were the first people to ever form a shadow board in the context we had. We struggled really hard with defining the role for ourselves. We struggled with getting projects going. We failed to get some things we wanted done and (in part because of that) we failed to win some people over. More often than not it was because we wanted to discuss and not do. We’d been trained as great diplomats who could come up with ideas and plans, who can research the pants off anything you need us to, but without the burning fire of a client we weren’t always the best do-ers. I wasn’t always the best I could have been. If I could go back and start this all again I’d want to be braver and bolder. In order to lead you have to go out on a limb to take a first step, knowing it might be wrong but also how much worse it can be if you don’t.

My favourite projects to work on, our careers project, the intranet, our exec shadowing discussions, were my favourites because we had a clear scope and we had a real drive to get something done. We applied what we knew of our expertise and drew on other people as experts in their own experiences.

If I’m ever a leader that’s what I would hope to provide. I would want to model clear communication and confidence in action (and responsibility with failure). I would want to acknowledge the strengths and diversity of those around me and amplify those talents, knowing I still have so much to learn. I would want to remember that things are what you make of them.

Now that I’m leaving the shadow board behind, I’m not sure what’s next other than focusing on trying my best at my day job. It’s changed my perspective and I think it’s made me better. But I don’t know that it’s made me want to have loftier ambitions.