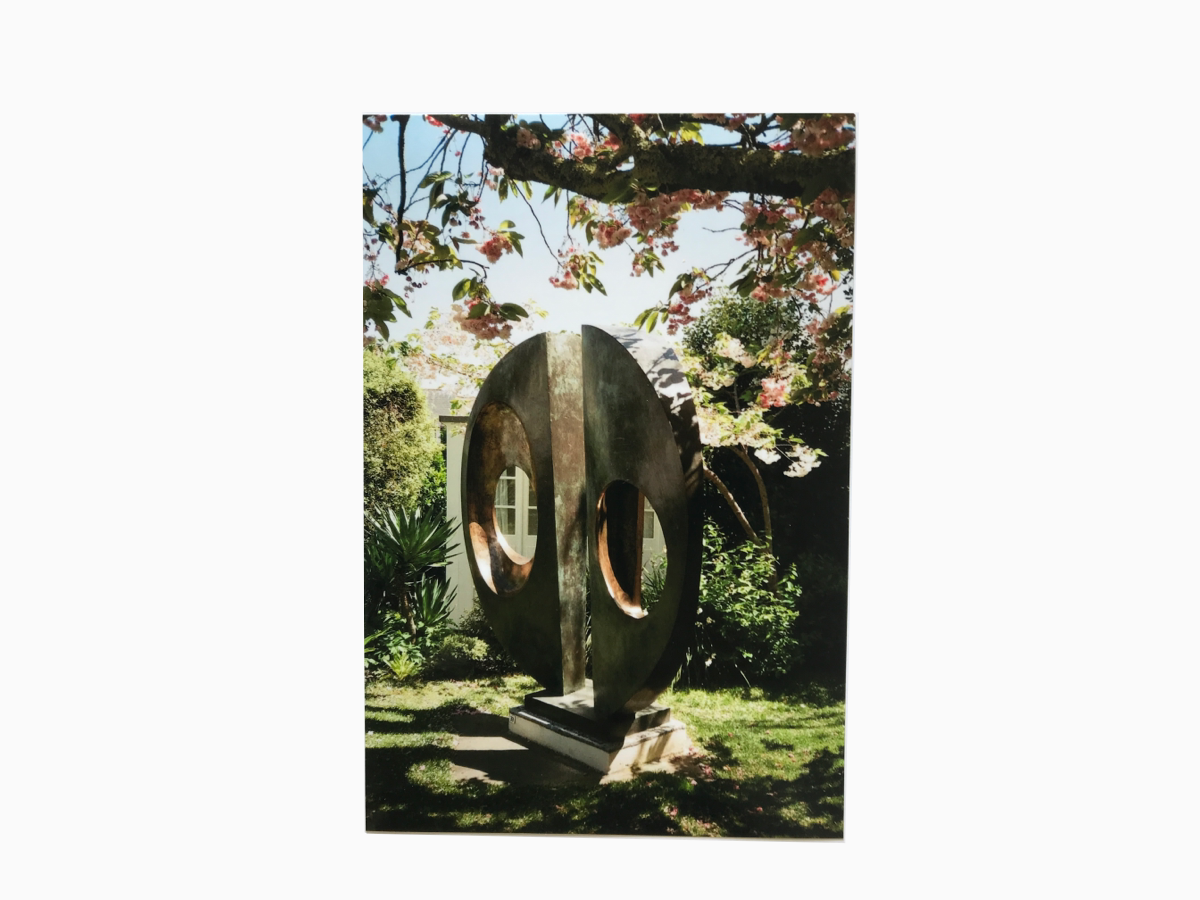

Barbara Hepworth is one of my favourite artists of all time. I’ve visited her sculptures up and down the country and there’s always something so present and grounding about them, that they make me feel better no matter how discombobulated I might feel.

So, I thought, I’d turn to her work to give me a bit of inspiration and to ground me in these strange times. I’ve not done many artist studies since I was at school. But there was always something liberating and perspective changing about trying to get under the skin of someone else’s work. Plus, my favourite blog posts are the ones that involve a bit of research. So, I’m going to try something a bit old school with this one.

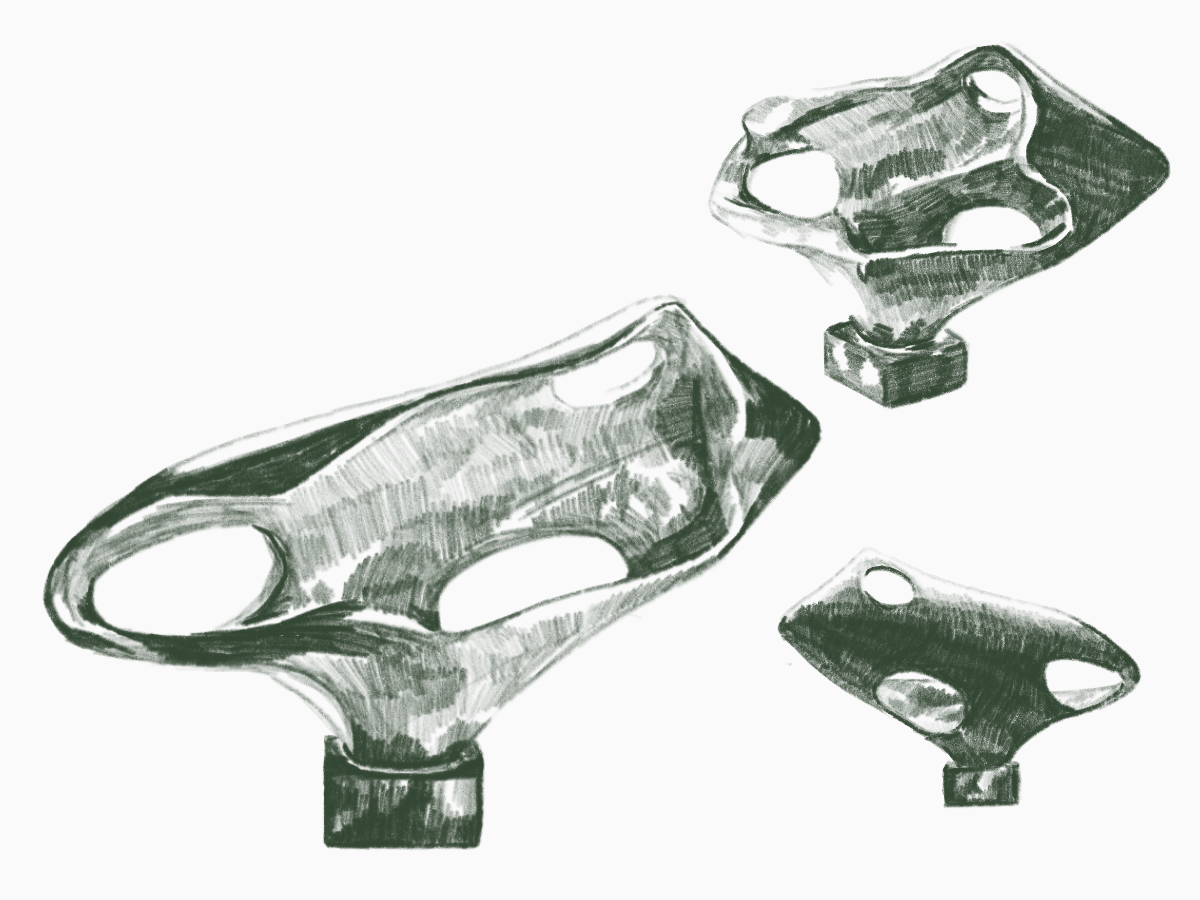

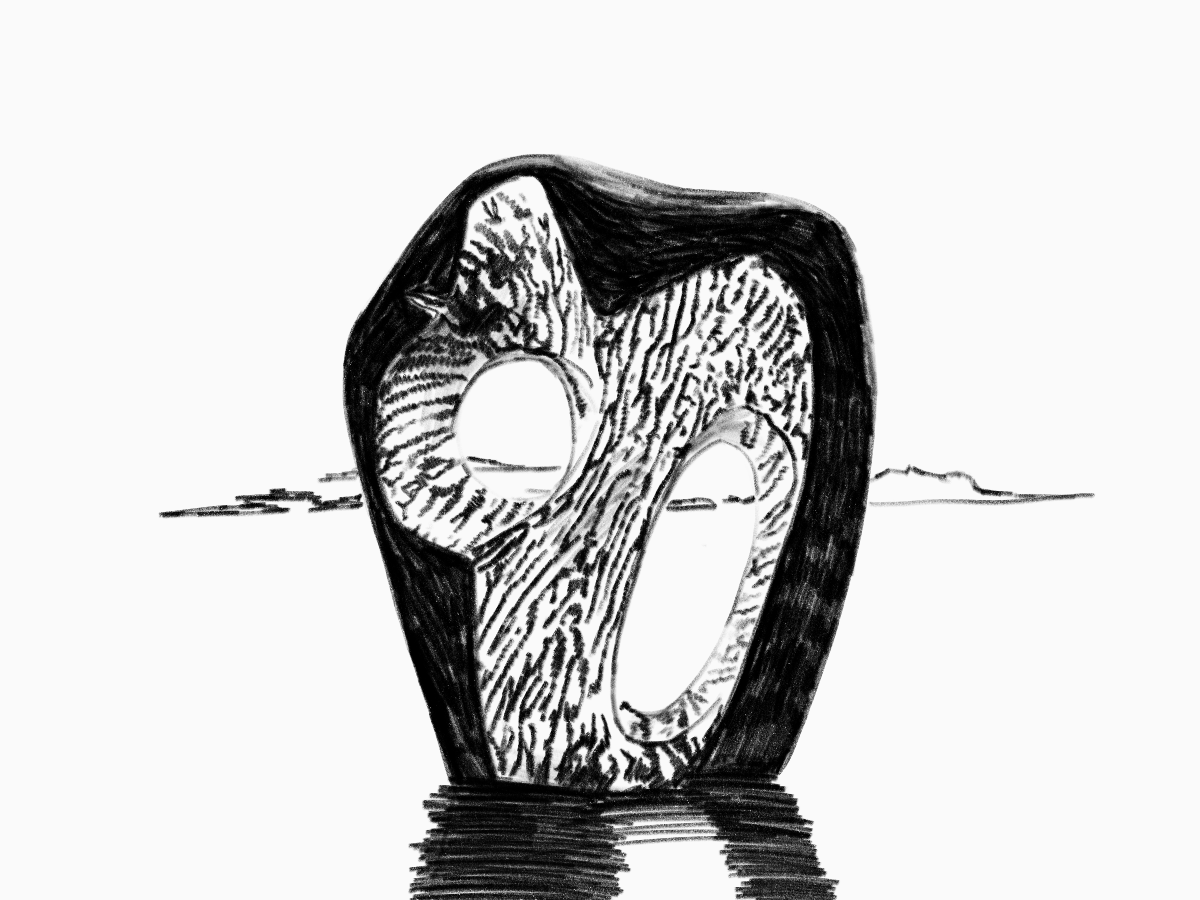

For those of you who aren’t familiar with Barbara Hepworth, she’s one of Britain’s most important twentieth-century artists. Born in Wakefield in 1903, she was a pioneer of organic abstract sculpture and is often discussed alongside her contemporary Henry Moore. She’s best known for her pierced Modernist forms which were made from alabaster, marble, bronze, wood, and aluminum and grew in scale throughout the years. Those sculptures were deeply connected to the human form but also the form of the landscapes they were made in whether that was West Yorkshire, Italy or St Ives.

There’s no one who can speak more eloquently about Barbara Hepworth’s work than the lady herself, so I’ve taken five quotes from her writings to see what I can learn about art, life and how to get the most out of them both.

Making is being

Extracts from Barbara Hepworth, A Pictorial Autobiography, Bath, 1971

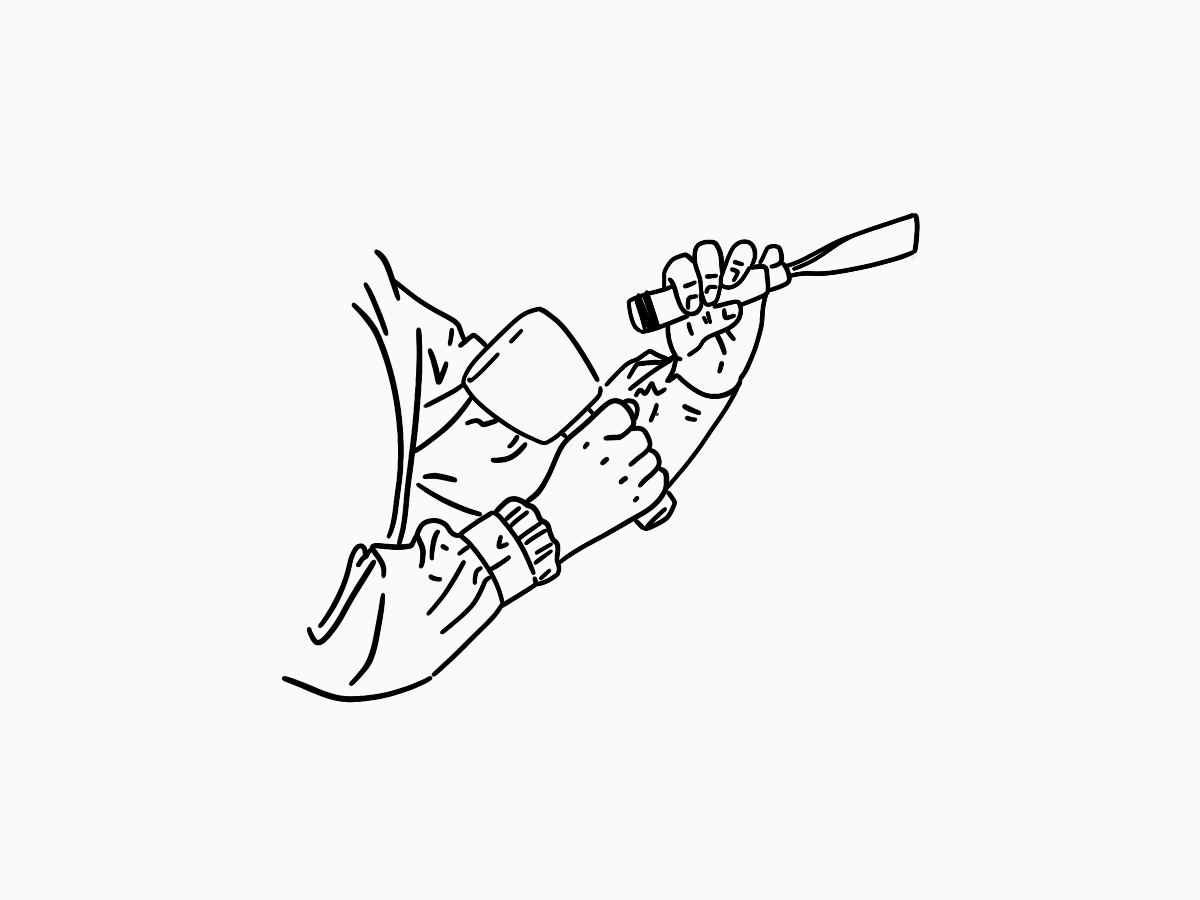

Hepworth was a leading figure in the the method of direct carving, meaning she made her pieces herself from her chosen material rather than making models for craftsmen to then turn into the final piece, as had been the norm. She spent years in Italy learning her craft and how to work with the materials. This connection between her work and her physicality, comes across as almost giddily empowering in her description. I’m always striving for that sense of being so truly in my body while making, and it’s a wonderful cry for craft and getting in touch with the power of connecting your “mind and hand and eye.”

Everything is contextual

Extracts from Michael Shepherd, Barbara Hepworth, London, 1963

First of all, I love that Hepworth made her sculptures to be touched and I am always fighting the urge to put my hands on the wooden pieces I see in museums. Second the idea that “there’s no fixed point for a sculpture, there’s no fixed point at which you can see it, there’s no fixed point of light in which you can experience it, because it’s ever-changing,” (First retrospective in 1968) is something that changed how I interact with both sculptures and the world more generally. The conditions that align around every experience we have with an artwork are different, meaning every viewing is unique. That’s the same whether the sculpture is a Hepworth or the lamp post outside your house. The more we make our experiences vulnerable to these changes in context and environment, the more life they have and the more variation we’re able to see.

Work with what’s around you

Extracts from ‘Barbara Hepworth – “the Sculptor carves because he must”‘, The Studio, London, vol. 104, December 1932, p. 332

One of the reasons Hepworth took up direct carving was so that she could work with the unique qualities of materials she was using. Their designs had to be harmonious with their substance and the making was a conversation between her desire and the material’s nature. Taking the time to understand what you’re working with, whether that’s “stones and woods”, people, or a space, should always be the first step in a craft. If you don’t know its strengths and its needs, how can you make the most of them? I think that’s also true in life more generally, you have to work with what’s around you and understand that the best “most direct way through” is dealing with a situation “according to its nature” rather than always what you thought would be best at first.

Our lives and our work aren’t separate

Extracts from Barbara Hepworth, A Pictorial Autobiography, Bath, 1971

While Hepworth “asked simply to be treated as a sculptor (never a sculptress), irrespective of sex” (Alan Bowness), it feels wrong to consider her work without the context that she was living through. Hepworth was a wife and a mother at a time when those things came with implicit and explicit expectations of domestic work. She took long breaks from making when she had to care for her children, and was only able to focus on her creative pursuits when supported by nannies or her children being old enough to care for themselves. But she saw these shifts in focus to and from her caring responsibilities just as part of a “rich life”. She was a woman getting the most out of her days. But in order to do that she had to find time, even in an unbalanced weighting, to have a little focus on each part.

Leaving space can make work fuller

Extract from ‘Approach to Sculpture’, The Studio, London, vol. 132, no. 643, October 1946

Hepworth is best known for her pierced forms, sculptures you can look, reach and sometimes even climb through. Opening up her pieces also “open[ed] up an infinite variety of” other shapes. Whenever I look through one of her sculptures, I’m taken back to that quote and the idea that creating space within something can make it so much fuller, whether that’s leaving space for interpretation and imagination in what you create or giving yourself space in your day. I think there’s also something poetic about seeing what you create as a lens for the world. The work isn’t the thing, it’s where you get to when you’ve gone all the way through it to the other side.

Those are just five (well six) of my favourite quotes and lessons from Barbara Hepworth. The longer you spend with any piece, the more you can give it your full attention the more you can learn about and from it. I really enjoyed taking this time to focus and be led by Hepworth’s writings on her own work, it felt like a personal conversation rather than a passing glance or skipped through algorithmic recommendation of what to look at next, pausing with intention felt particularly important right now. I’d encourage anyone to do it if they can, whether you pause with your favourite artist, craft, nature or something else.