I’ve been writing a fair bit about time in my newsletter recently, about the power of time, about how time is constructed, about how we can choose to use our time to nap all we want.

It was all set in motion by a trip home. Where I grew up everything shuts between 5pm and 8pm. We’re more like 30 minutes away from anything you might deem a high street. So, when I went to take my dog for a walk at around 7pm on a Friday I saw hardly anyone.

Whereas where I live now, the high street about 30 seconds from my house pretty much never closes. It will be as busy at 1am as it is at 1pm. As such, I’ve become used to walking out on an evening and seeing people, or running errands after dinner.

We adapt to the environments we’re in, and those environments include their own rhythms. I had come back to York with my London rhythm and felt completely out of place despite knowing the streets as well as I know any in the capital.

A social sense of time had impacted how much I felt a part of a community.

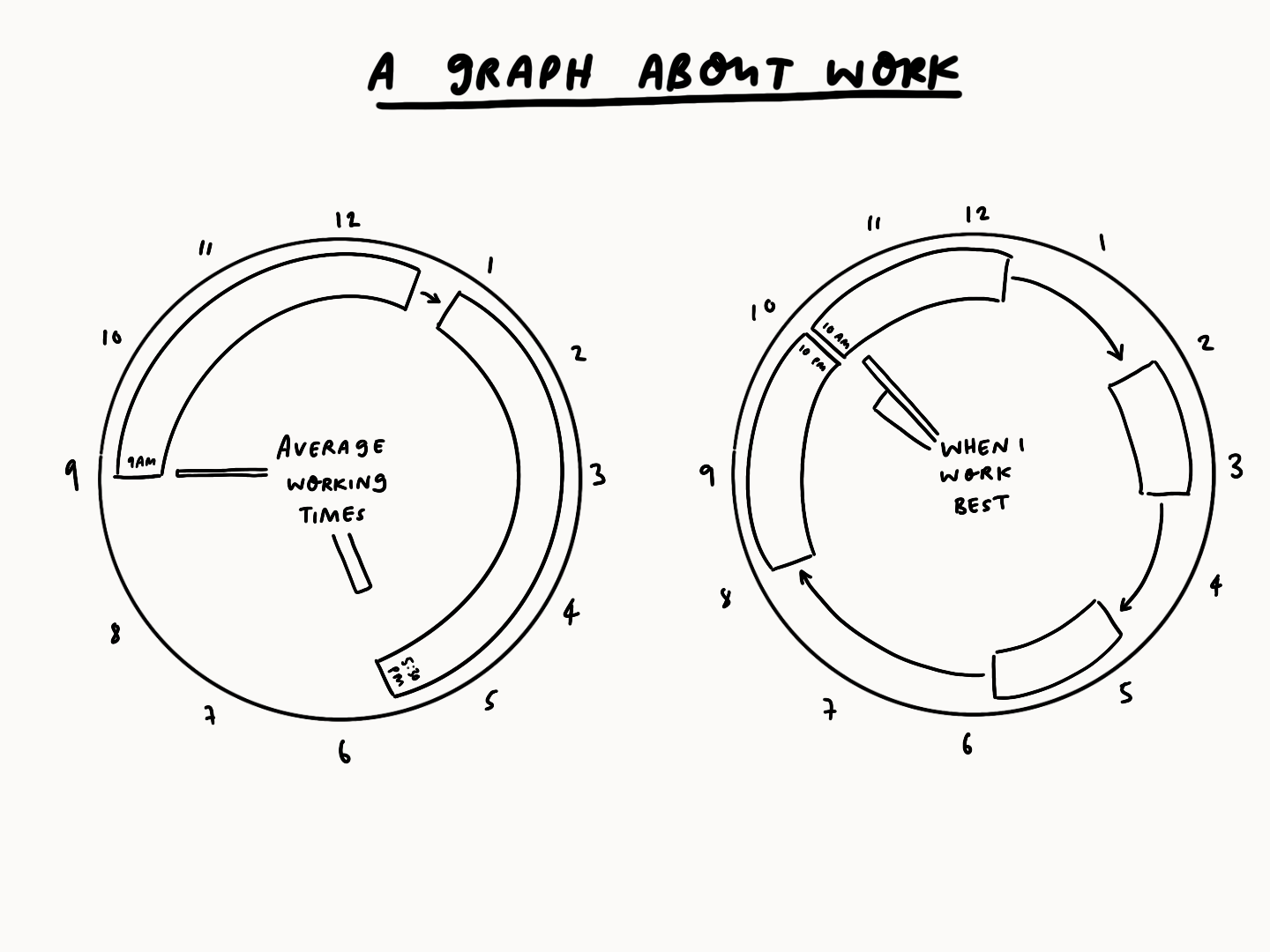

But those rhythms can easily become something more solid. Think of how Henry Ford’s standardised work week has permeated across the world and into our psyches such that working 9-5 isn’t just a way to make a livin’ it seems to be the only way, despite lots of studies arguing perhaps the set 40 hour week isn’t the most efficient use of our time.

Whenever I think about the power of time and our control or lack of control over it, I find myself playing out a scene from Shakespeare’s Richard III. King Richard is about to have all of his plots unravelled, to lose his control, his kingdom and his life. But first, in a preparatory scene, which is (wrongly in my opinion) sometimes cut from certain editions, Richard yields his sense of time.

“KING RICHARD III

Well, but what’s o’clock?

BUCKINGHAM

Upon the stroke of ten.

KING RICHARD III

Well, let it strike.

BUCKINGHAM

Why let it strike?

KING RICHARD III

Because that, like a Jack, thou keep’st the stroke

Betwixt thy begging and my meditation.

I am not in the giving vein to-day.”

-

Act 4, Scene 2

Richard had controlled the pace of the world around him, but now his “meditation[s]” are being interrupted by Buckingham and more than that, he admits defeat to the ticking clock. What I’ve always found interesting about this passage is that Shakespeare wrote it just as clocks had first started to invade people’s homes. For the first time ever, personal spaces had visual and audible reminders of regimented social time. I’ve always wondered if this scene was inspired by this change, by an impact having a clock ticking away as he wrote had on Shakespeare. But who knows.

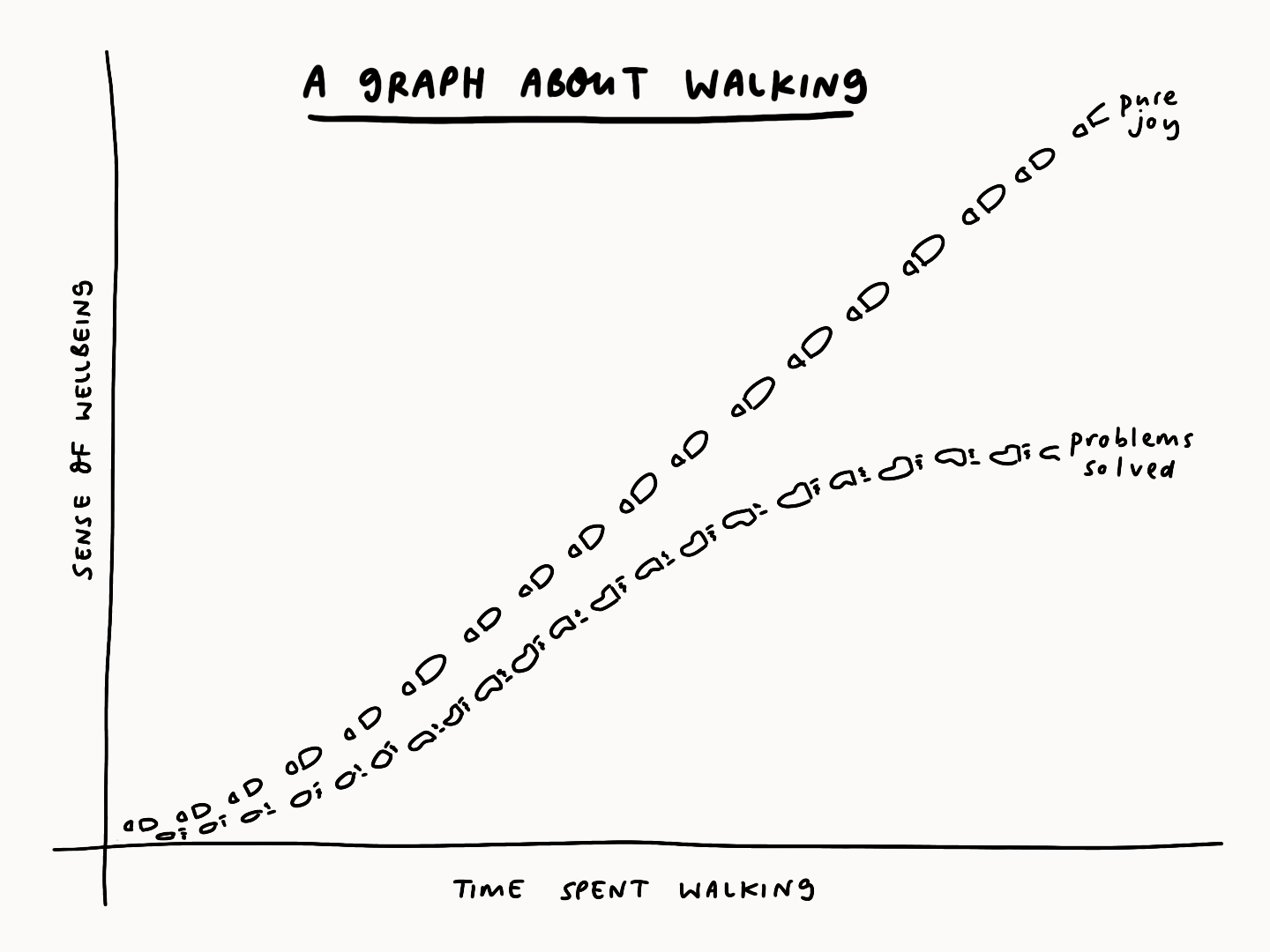

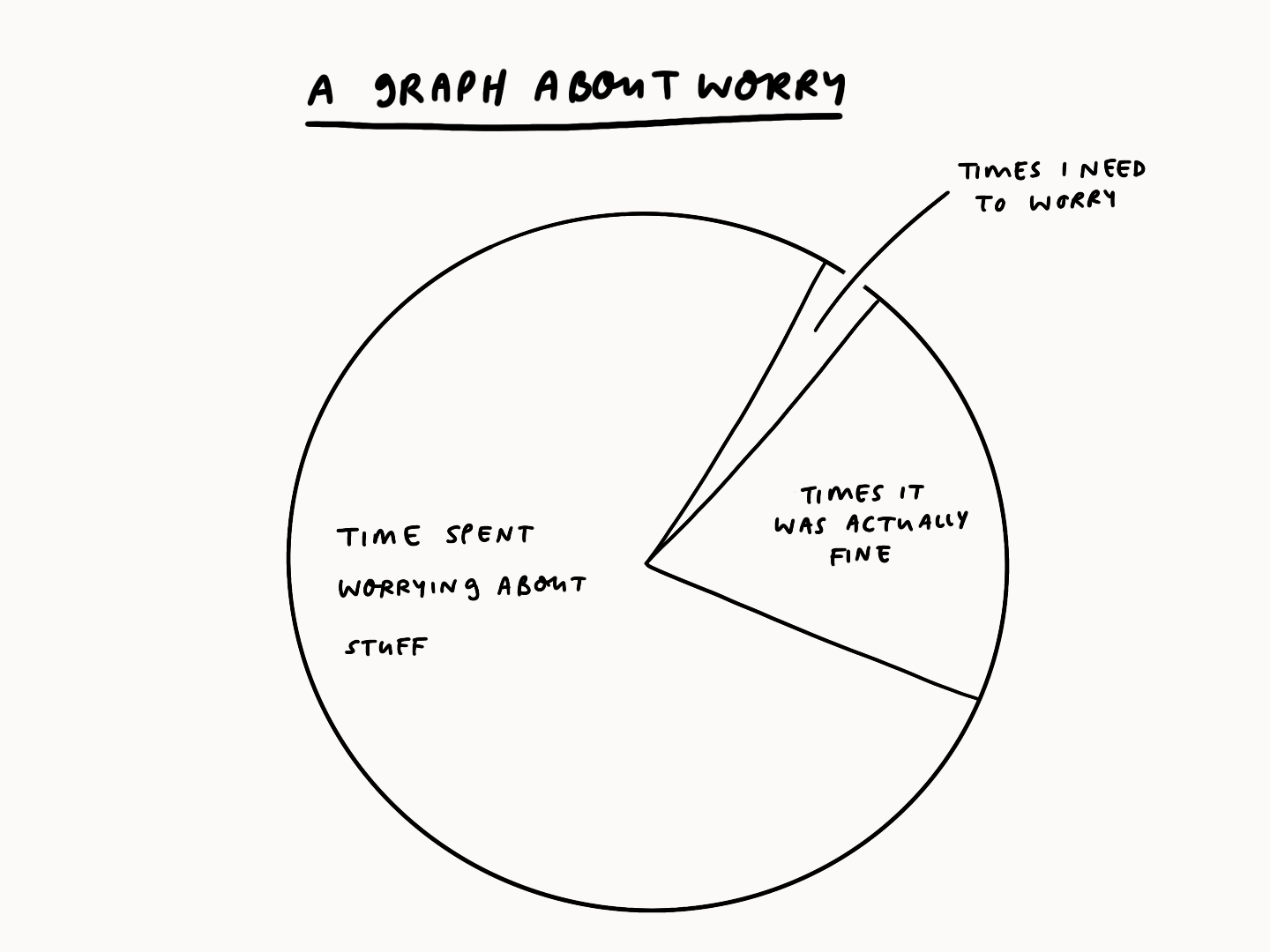

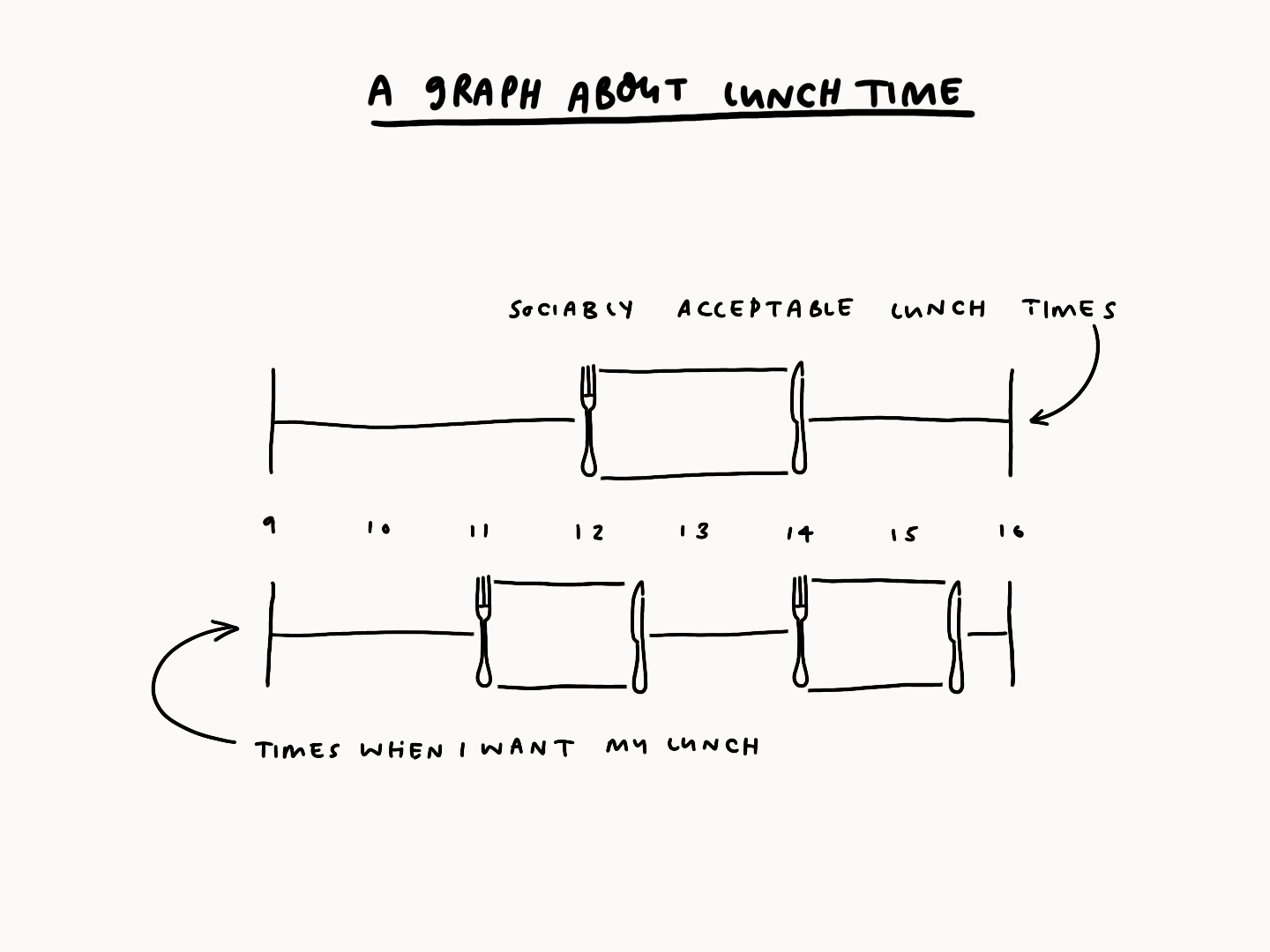

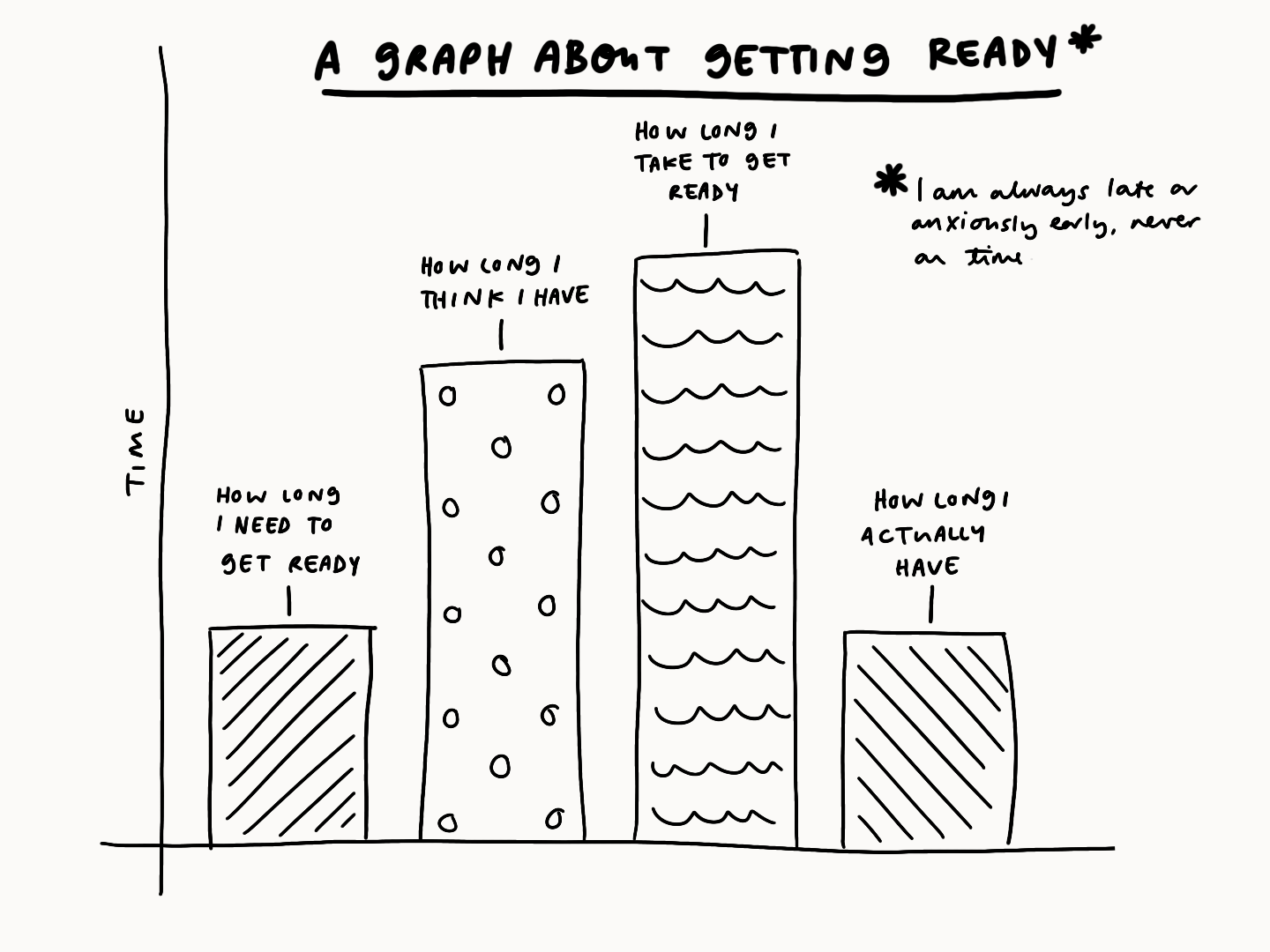

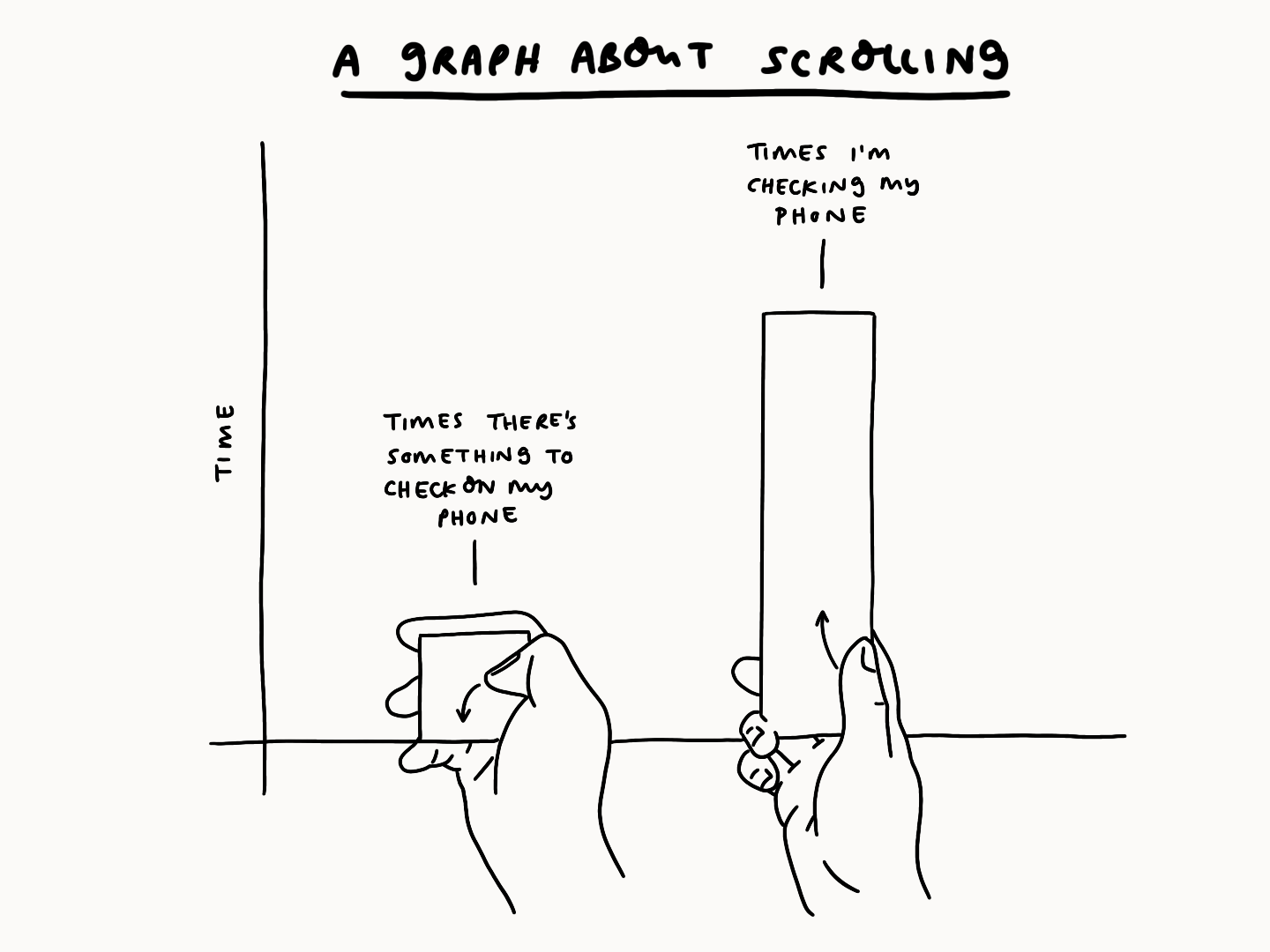

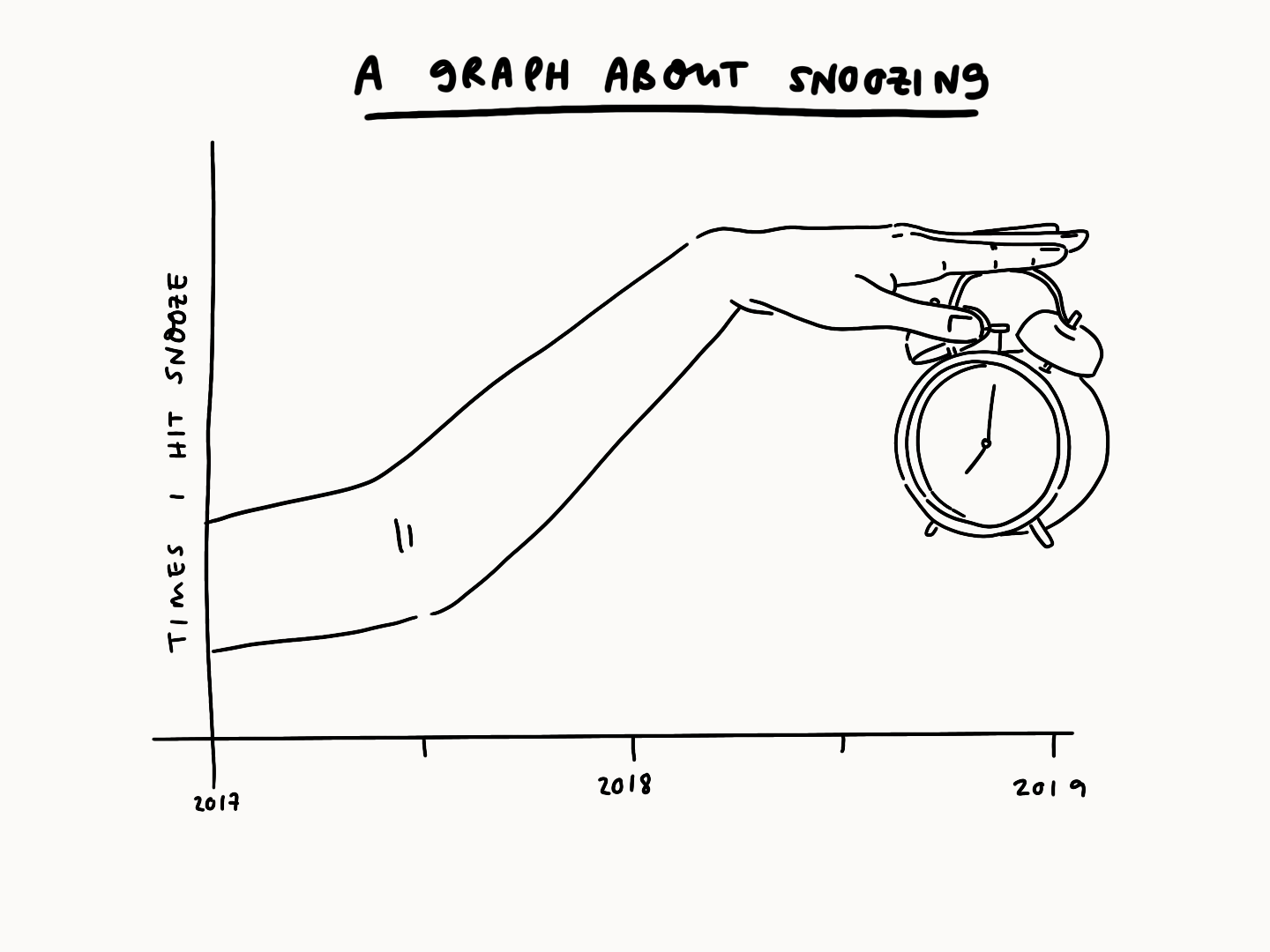

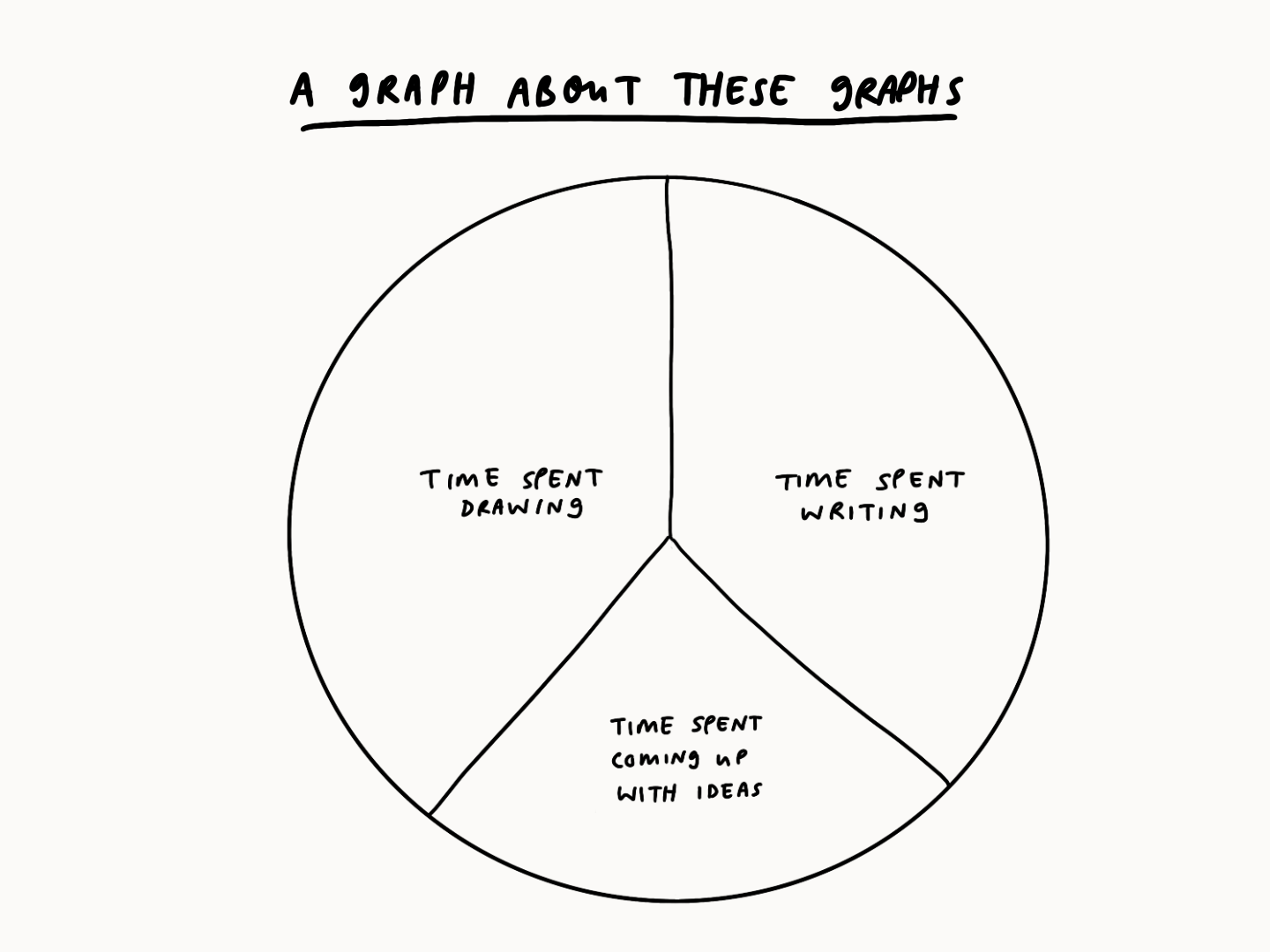

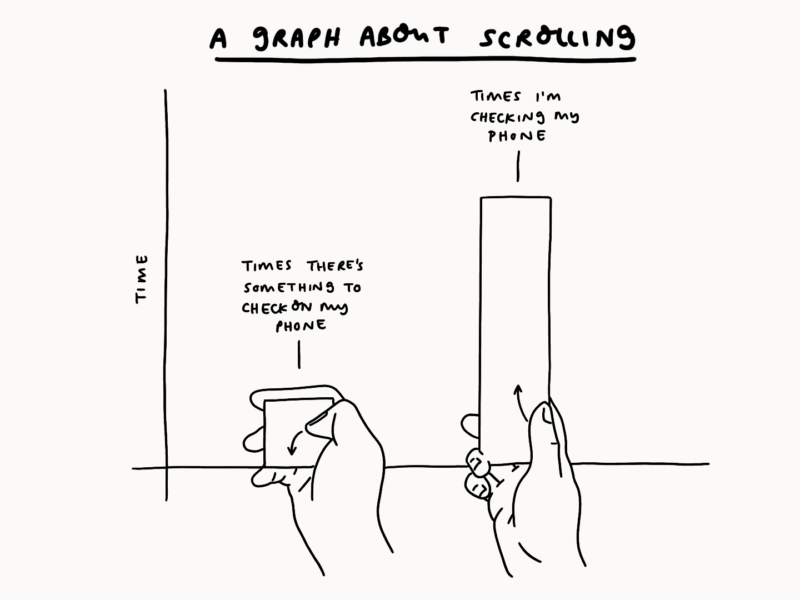

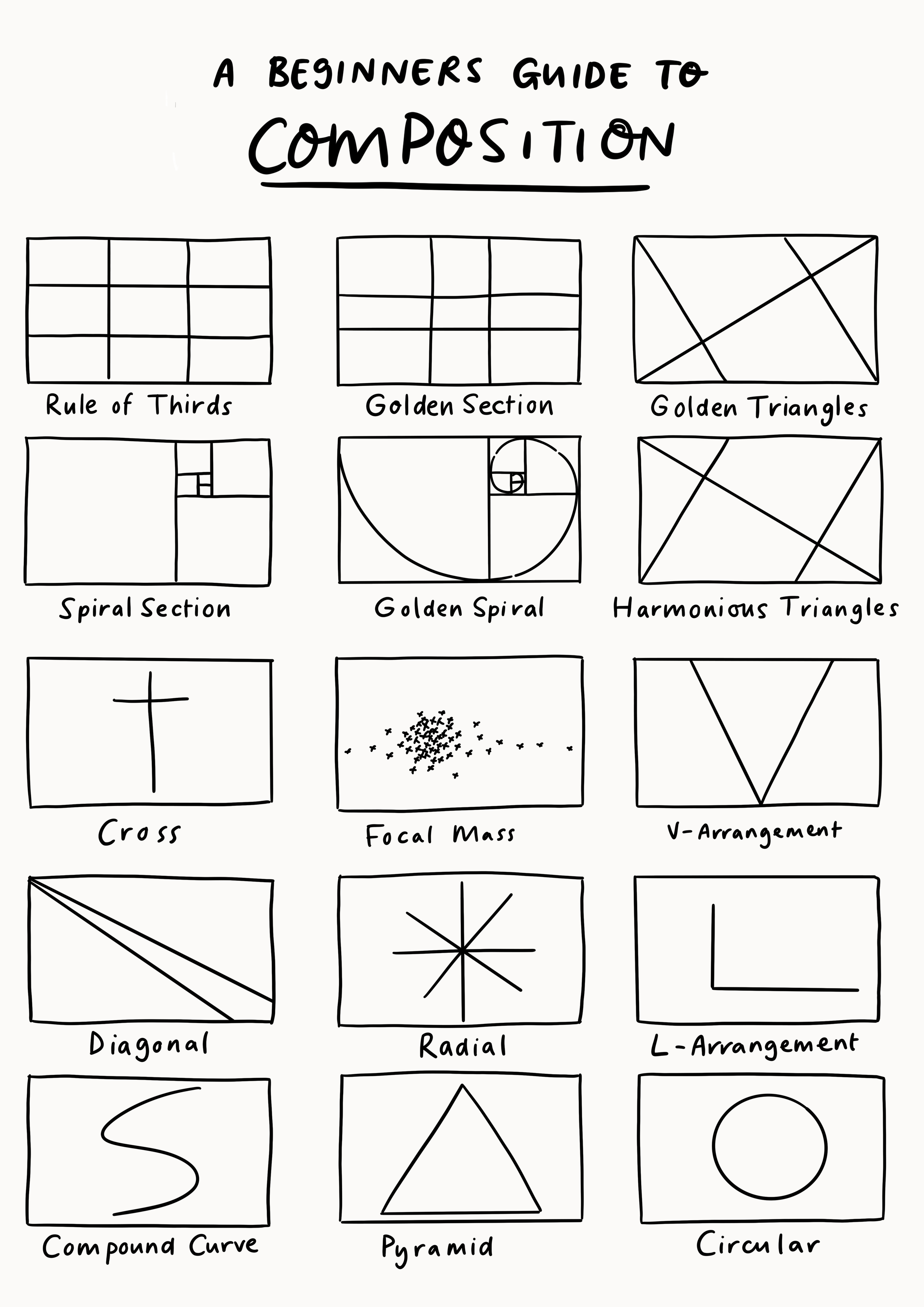

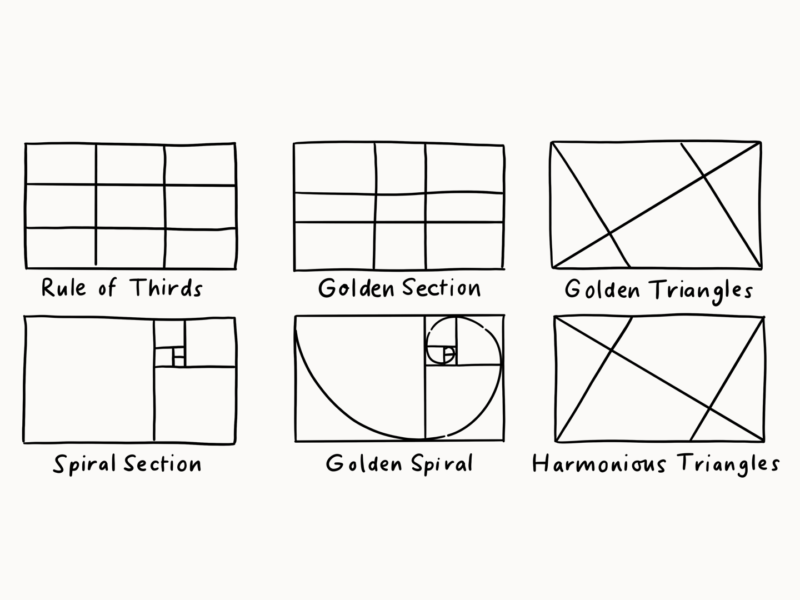

That scene also makes me think about how we mark time visually on clocks and audibly in ticks, tocks and ringing bells. Today, I wanted to play around with how I represent my time. I wrote a few ‘how I manage my time’ posts back when I first started this blog, but I didn’t just want to do that again. Instead, I wanted to challenge myself to make something visual, because telling visual stories is something I want to do more.

So here goes nothing…