I picked up a copy of The Shepherd’s Life as an impulse purchase. I liked the cover. I’ve spent my summer, and often winter, holidays in the Lake District since I was very small and the image of a green fellside conjured up some of that nostalgia as I walked past a table in Waterstones.

I’m so glad that cover spoke to me. Sometimes you can judge a book by its cover. The Shepherd’s Life: A Tale of the Lake District, by James Rebanks, is a truly glorious book. A memoir of both Rebanks life and fells he has spent that life farming is a captivating read about a captivating landscape, that’s at once personal and pastoral.

The Shepherd’s Life isn’t told chronologically. Instead, Rebanks shares his memories in fragments that are loosely sorted into seasons. These fragments jump between his childhood, adolescence and present-day adulthood and cover everything from his memories of his grandfather to the ins and outs of shearing a sheep.

As someone who has walked many of the fells mentioned in its pages, it was so interesting to read about them from the perspective of someone who has worked them for a lifetime. Rebanks’ is a story I had only ever briefly considered when asking my mum as a child how the dry-stone walls were built, when counting all of the different markings on the sheep we spotted, when marvelling at the intelligence of the dogs I saw working the hills. Getting to read such an in-depth account of a way of life I had only ever glimpsed at by proxy was such a treat.

That said, I don’t think The Shepherd’s Life is only for those who already love the Lakes. You don’t need to have visited the Lakes to imagine them, or to imagine Rebanks rural life because he puts it all on the page. One of the major reasons people say they read is to get an insight into someone else’s way of life, their way of thinking, and that’s exactly what The Shepherd’s Life offers. I think what struck me the most about The Shepherd’s Life is the way that it made me reflect on my own life, and how my own environment had shaped me. Not to over-egg this review but I genuinely think this book changed my life a little bit, or at least how I think about it.

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

- What do you think about how the book flows? How do you feel about its fragmentary structure?

- Rebanks’ account of his understanding of his home and his work is inextricably tied to his understanding of his family. Reflecting on those unbreakable links, how has your own environment and family shaped you?

- The book almost starts off in opposition to the reader, how do you find the constant distinctions of ‘them and us’ affect your reading experience?

- If you’ve ever been to the Lake District, or anywhere similar, as a tourist, how does reading the account of someone who works the land change your opinion on the place you visited?

- The Shepherd’s Life tells a story that isn’t often heard, as Rebanks often reminds us, what lives and stories have gone unnoticed in your own environment? Is there any way you can find out more about them?

IF YOU WANT SOME FURTHER READING TRY…

- There’s a lovely review in the FT by Melissa Harrison

- Author of On The Crofter’s Trail, David Craig has also penned a great review if you want a better sense of the book, this one for The Guardian

- I really enjoyed reading The Durham Book Group’s thoughts on the memoir

- But I think the best piece of further reading I’ve found is the interview Stephen Moss of The Guardian did with James Rebanks, it really gives you an extra insight into the author and his way of life from an alternative perspective.

IF YOU WANT MORE BOOKS LIKE THIS HAVE A LOOK AT…

- James Rebanks’ The Illustrated Herdwick Shepherd

- Roger Deakin’s Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees

- Helen MacDonald’s H is for Hawk

Ernest Hemmingway’s The Moveable Feast- Alice Oswald’s Woods Etc.

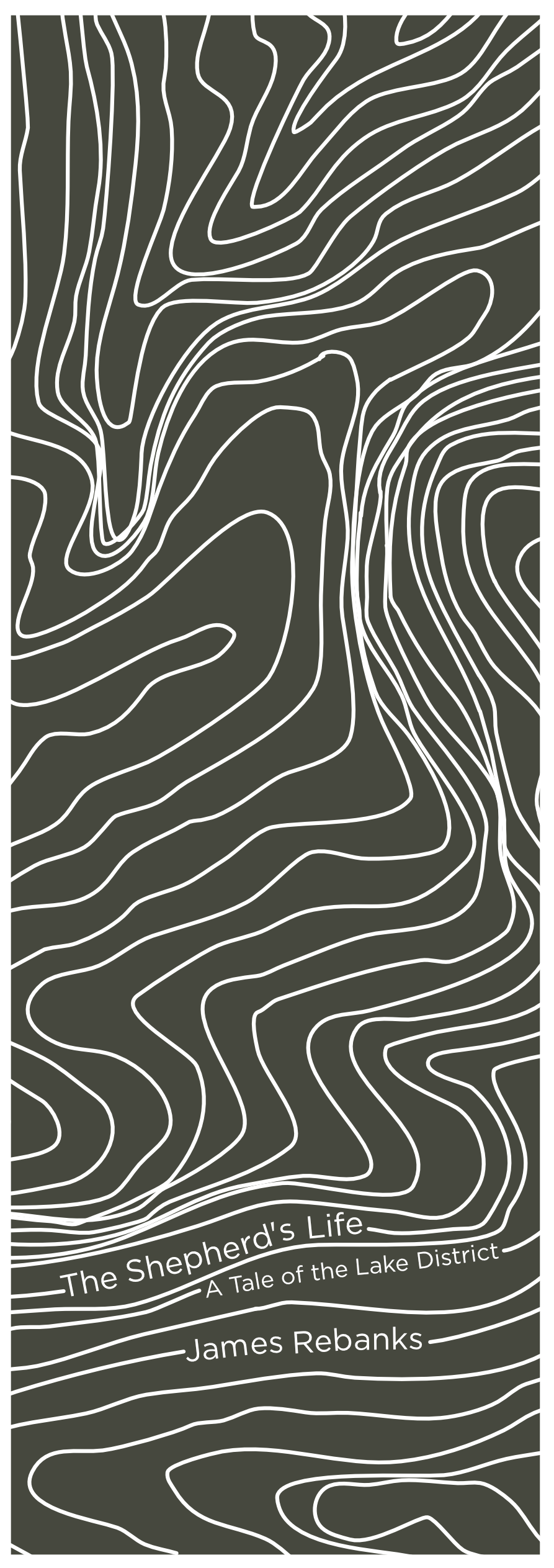

Why not use the Shepherd’s Life bookmark I designed to keep your place as you read? It even features the topology of a section of the Lakes Rebanks discusses. You can print and download it for free here.

As ever, let me know if you’ve read The Shepherd’s Life, or if you have any recommendations for what I should be reading next.

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

Groff’s choice to write her novel in two halves isn’t revolutionary but it is rarely done so well. As you read, it just makes sense. The second point of view adds so much to the novel and to the richness of the characters. By the time you reach the half way point, you are so invested in Matilde and Lotto, you’re so close to their story, it doesn’t feel like a radical shift or turn but just a step deeper into their relationship.

Groff’s choice to write her novel in two halves isn’t revolutionary but it is rarely done so well. As you read, it just makes sense. The second point of view adds so much to the novel and to the richness of the characters. By the time you reach the half way point, you are so invested in Matilde and Lotto, you’re so close to their story, it doesn’t feel like a radical shift or turn but just a step deeper into their relationship. SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ…

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ…