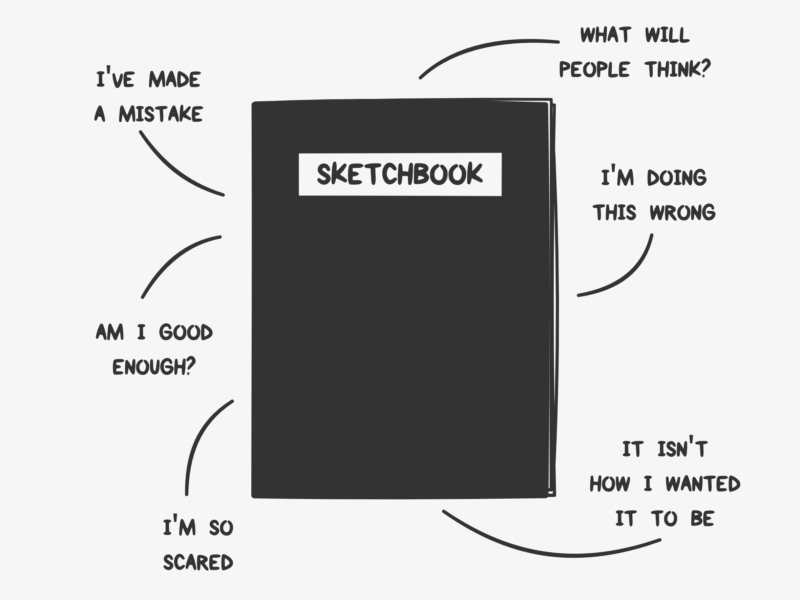

A little while ago I wrote about the fact that I hadn’t properly used a sketchbook in quite a few years. The idea of it just made me too anxious. After an education where every page was marked and every rough work highly calculated, the idea of just having a sketchbook seemed much too daunting, especially being surrounded by images of gorgeous artist sketchbooks on social media.

I felt so far away from being able to produce a sketchbook I was happy with that I just didn’t try.

But I knew I was missing out on something. I had enough notes and thumbnail sketches on random bits of paper that I knew I could probably do with somewhere to keep my ideas. I also had a real desire to start making, physically making, more with my hands again.

Skip forward a few months, I’m now on my second sketchbook and using mine every day. It has truly become an invaluable resource for me, and a space to play in.

So how did I get here? And how can you overcome sketchbook anxiety?

DON’T BUY A NICE SKETCHBOOK

The sketchbook I started in was a funny shape, was a bit battered, and cost me about £3 because it wasn’t the prettiest on the shelf. Normally something like that might have bothered me – I’m the kind of person who doesn’t like to crack the spines on their books. But, in this case, it was perfect. Having an already beaten up sketchbook meant that I didn’t feel precious about it. There was no investment to ruin. I’ve just started a side sketchbook for a single project I’m working on made up of scrap paper I have just stapled together. Start with something you don’t mind getting messy in, it gives you so much more freedom.

RUIN THE FIRST PAGE

On that same note, mess up your first page. Or, don’t even start on the first page. There’s this weird anxiety over getting the first page right in any new book, that I think comes from being little and trying to write your name as neatly as possible on the front cover of exercise books. When you just get past the first page you set up the book as a place for experimentation. Paint your first page all one colour. Do a little scribble in the middle. Write the date or say hello. Just do something silly that doesn’t have to be neat.

TRY A DIFFERENT MEDIUM

Another way to free up your anxiety over having to produce something great is using a new medium. In my sketchbook, I decided just work with watercolours, something I hadn’t done since I was in school. I also painted freeform abstract pieces. This completely took the pressure off anything I created being ‘good’ and instead made it about the process of learning and painting, and just got me into the habit of creating. Using a new medium is also just a great creative practice for changing up how you think about and approach a work.

MAKE IT ABOUT PROCESS

As I mentioned above, I focused on the actual process of painting. How it felt to put colour on the page, and I was led by my hands. I wasn’t too worried about the outcome, instead I just focused on doing, on painting. The outcomes I produced did get better, but purely because I became more confident in what my hands could do and just trusted the process. Your sketchbook is thinking space more than anything else.

DO SOMETHING EVERY DAY

Another important element of making my sketchbook about process was committing to make something every day. It didn’t matter what I made as long as it was something. Once I got into the habit of setting aside 20 mins to make something (this did take a little while) I found myself looking forward to using my sketchbook, and once it was half way filled actually feeling good about it. Then it became about having some thinking time, or a chance to work through a problem away from the computer. Doing a tiny bit every day adds up, and it’s so much harder to abandon a sketchbook once you’re ¾ through.

DON’T SHOW ANYONE

There’s a lot of pressure to share everything you do on social media, but sometimes having something that’s just for yourself can make it even better. By not sharing my sketchbooks (until now) I felt far less pressure to produce work that would align with the rest of my finished outcomes and I got to have something that was just mine.

WORK OUT WHAT YOU ACTUALLY NEED IT FOR

Everyone’s sketchbook is different, because everyone’s process is different. It’s all well and good seeing pictures of sketchbooks you love and taking inspiration from them, but make sure you’re using yours in a way that works for you. For example, I adore Mark Conlan’s sketchbook images, but working up full colour drawings doesn’t really fit into how I work. Instead I much prefer thumbnail sketches, note taking, and painting my abstracts. But I love how he focuses on a single image per page, so sometimes I just do that but with my own pieces in my own style as the focus.

REMEMBER IT’S A RECORD

Whether you hate what you’re drawing right now or you love it, it is a record of what you’re doing, what you’re thinking, right now. There is something so satisfying about flicking back through the pages of my books and seeing how my work has changed. If you don’t like it right now, don’t worry, turn over the page and start something new – don’t erase it.

That said, it wasn’t until Gideon Sundback took a stab at the zipper that it got the interlocking teeth we rely on now to keep our trousers up. Sundback’s interlocking teeth didn’t come apart as easily as Judson’s meaning his was a more secure fastening. Not only that but, he also increased the number of fastening elements to 10 per inch to further increase the security and to make the sliding motion smoother. Sundback patented his design in 1917, and we’re still using almost exactly the same design 100 years later.

That said, it wasn’t until Gideon Sundback took a stab at the zipper that it got the interlocking teeth we rely on now to keep our trousers up. Sundback’s interlocking teeth didn’t come apart as easily as Judson’s meaning his was a more secure fastening. Not only that but, he also increased the number of fastening elements to 10 per inch to further increase the security and to make the sliding motion smoother. Sundback patented his design in 1917, and we’re still using almost exactly the same design 100 years later.